Why this Sandbox?

Like millions of other schools around the world, schools in refugee camps had to close with the onset of Covid-19. Jusoor, a charity providing help to Syrian refugees, moved quickly to set up WhatsApp-based learning for children in refugee camps in Lebanon.

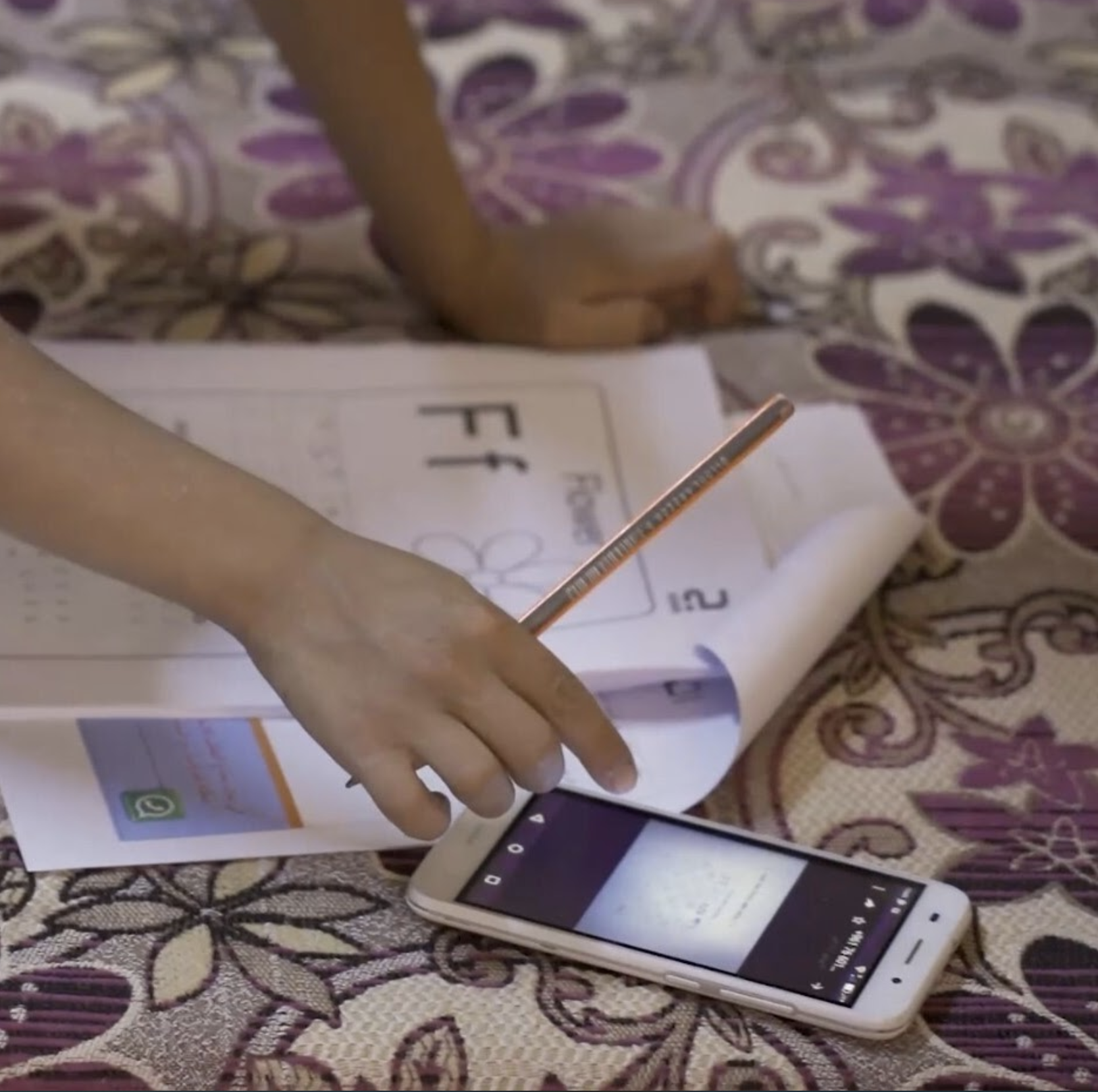

WhatsApp became a temporary classroom. Teachers used it to distribute assignments, and children used it to submit their work. While this idea seemed to be working, the response rate varied a lot – some children were engaging 20% of the time, others 60%.

This idea resonated with the recommendations of EdTech Hub’s Messaging Applications Rapid Evidence Review, that messaging can be used in a range of learning activities, through a combination of sharing educational materials, with interaction between pupils, peers, caregivers and teachers.

In partnership with UNHCR, the EdTech Hub joined Jusoor to run a sandbox focused on delving deeper and gathering more evidence on the WhatsApp model.

Our shared goal was to answer: How could WhatsApp best be used to provide effective education to refugee children?

Quick Facts

- 68% of refugee families have a smartphone, but that didn’t always translate into participation.

- 186 families given access to $25 cash – choice to keep it, or use it on a device or data.

- 28% increase in engagement of children whose parents chose to rent a phone and buy a data card.

Keeping Teachers and Students Connected

WhatsApp is a well-established and very widely used communication tool among refugee communities. About two thirds of the families in the Syrian camps in Lebanon own a smartphone. Jusoor’s initial decision to use WhatsApp for remote learning was simply a case of making use of what was already there.

At first the idea was to keep teachers connected to their existing students. As school closures continued, new students were enrolled and joined the WhatsApp classroom.

In order to assess the impact of the programme, the team observed some of the WhatsApp lessons by joining the class WhatsApp groups. Teachers were scored on things like their lesson plans, the videos they created and the feedback they gave to the children. These observations confirmed that the majority of teacher’s were delivering effective remote learning.

At the same time, we conducted a review of the existing research and evidence on the use of messaging and virtual learning environments. We found that WhatsApp provides all the key functionality needed, with the notable exception that children cannot be observed during assessments.

Our next priority was to investigate the varied engagement levels. One hypothesis was a simple lack of devices; another that parents in refugee households weren’t making children’s education a priority. As always, the reality was more nuanced and complicated than that.

An initial survey revealed that 68% of households did have a smart phone. Yet, this did not automatically translate into children having access to that phone. There were also many who owned a phone that had to be shared between parents and several children. In other cases, some families that owned a phone struggled to afford data packages from phone service providers.

As for prioritising education: in many cases, children who were missing out on education were doing so because they were expected to find work to boost family income. We found ourselves thinking about these problems, most of them symptomatic of the daily reality of living in a refugee camp. What could we do to alleviate them?

Money Talks and Money Texts

In one camp, Jurahiya, we offered families simple no-strings grants of $25. The money was theirs to spend however they wished, and one option was to spend it on renting a smartphone, or buying a mobile phone data package. As a result of distributing the cash, engagement with WhatsApp learning increased by 16%.

A majority of families (62%) decided to use cash on a combination of device and data rather than keeping it.

Combining both phone rental and data was the most impactful option – it saw the highest increase in engagement (28%). Almost all parents (99%) were satisfied with it. On the other hand, the cash only option only saw an 8% attendance engagement.

These cash grants, and the choice to access devices and data, made a noticeable difference: they had the biggest effect on the students who had previously had the lowest engagement.

Parents Need Practical Help

We also wanted to test cheaper alternatives that might impact children’s engagement. For example, evidence from work such as the Smart Buys suggests that information and positive messaging can be effective.

The sandbox team were aware that refugees get a lot of information and advice from many sources, via WhatsApp and other communication apps on their smartphones. In some circumstances, families can feel overwhelmed with incoming advice and information, to the point where it can become easily overlooked or ignored, especially if it’s generic. It was important to make sure the advice given was specific, actionable, and tailored to local circumstances.

Jusoor designed tailored information to send to parents, giving them tips on practical things they could do to help children learn at home. For example, how to give children a space to work and concentrate in. This isn’t always very easy in refugee accommodation, where a family might be sharing very limited space.

While this campaign did not translate into an increase in attendance over Whatsapp, 67% of parents found the advice helpful and adjusted behaviour as a result.

Parents said the advice they had been sent felt very relevant to their circumstances and experiences; it was genuinely useful for them. One parent said of the advice they were sent: “It’s like you’re sitting in my head!” – the Arabic equivalent of “You’re reading my mind!”

More research is needed to understand if the quality of the children’s learning has indeed improved as a result.

What We’ve Learnt

- WhatsApp is a viable option for teaching remotely during the pandemic.

- Refugee parents value their children’s education but need support to ensure they can access it.

- People need practical advice on things they can do to enable learning.

Recommended Reading

For more on positive messaging to increase participation in education read: Cost Effective Approaches to Improve Global Learning by Global Education Evidence Advisory Panel.